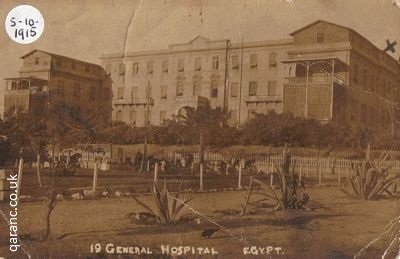

The most memorable

account I can think of about the BMH Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt, is Roald’s

Dahl’s in Going Solo. Dahl is best known for having written Charlie and

the Chocolate Factory, but long before Charlie,

Roald Dahl was a pilot in the RAF during World War Two (he was also a secret

agent, afterwards, but this doesn’t matter at the present); he crashed his

Gloster Gladiator in the desert and his face was reconstructed in Alexandria. I’m

going to guess that very little had changed since 1915, when allied soldiers

were being sent there from Gallipoli.

|

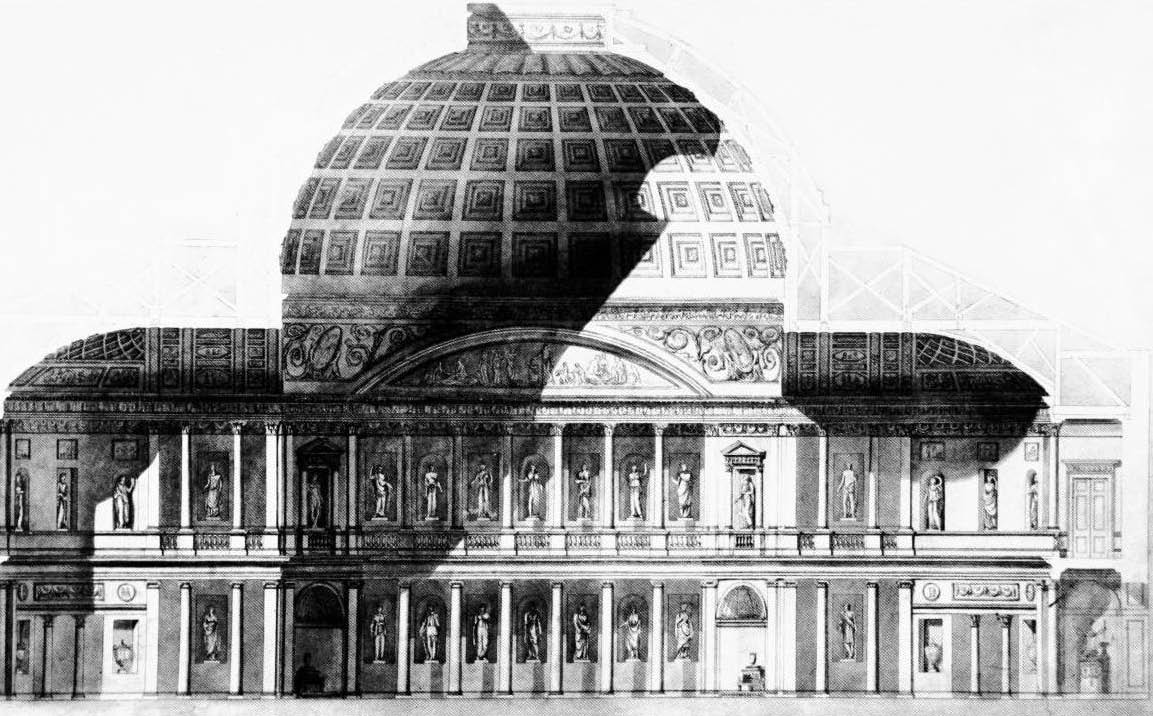

| Yale Commencement program,1911 |

|

| Archimedes' 'eureka!' moment, when he discovered how to determine the volume of an irregularly shaped object. eg: a crown He once said that if he had a lever long enough, he could move the World. |

Galen, one of the very greatest medical

researchers of all time, studied there, but unfortunately, the fire that destroyed

the Library, also destroyed the medical school. Time wiped away the Musaeum, yet the learning and knowledge

that went on there were not completely lost; today our understanding of the

world- of physics, engineering, chemistry, mathematics and medicine- is firmly

built upon the stones these thinkers carved out of the rock.

|

| The Tower of Hercules in Spain is an ancient Roman lighthouse built along the same lines as the Pharos of Alexandria |

Alexandria is such a strategic locations with its

two big harbors, it’s hardly surprising that it played an important role in

both World Wars. It served as a British command center, and for thousands of

injured soldiers, it was an oasis in the desert, a place where they returned

from the front line, little knowing that the methods used to treat their injuries

were based on the hard won knowledge of thinkers who had stood on the same

ground a thousand years before.

It was from Alexandria that the second letter from

Martin was sent. I wonder if he knew the history of the place. Of the Pharos,

the giant lighthouse that had once lighted the way of a thousand ships. And of

the Musaeum, which shaped the world

that came after.

I will stop talking now and let you read Martin’s

letter. Please bear in mind that he describes some injuries, so if you are

squeamish, proceed with caution. Like the last, original spelling and punctuation

have been preserved.

No 19 General Hospital

Alexandria

31st Aug

Dear (great-grandmother’s

name),

I wonder if you ever got my little note written from the hills.

Well if you did this is the sequel. I have been one of the lucky ones

and still am to be writing this note, but they got me alright. No I in the left

thigh and No 2 a little later on, broke my left arm.

This was on the 10th and I am down splendidly. Blood poisoning all

gone, & beginning to sit up and take a little nourishment.

I hope to be able to go home in about a fortnight. And shan't I just be

glad to see the old place again.

A year's soldiering is pretty strenuous!

But fellows are really fighting splendidly, especially the Australians

& New Zealanders.

Some of the positions are like going up the side of a house, and

directly one shows an eyelid you get shrapnel, machine gun and rifle fire

simply poured at you. If I come through this show and I ever see a man shooting

a rabbit again, I'll kill him. I could tell you quite a lot of interesting

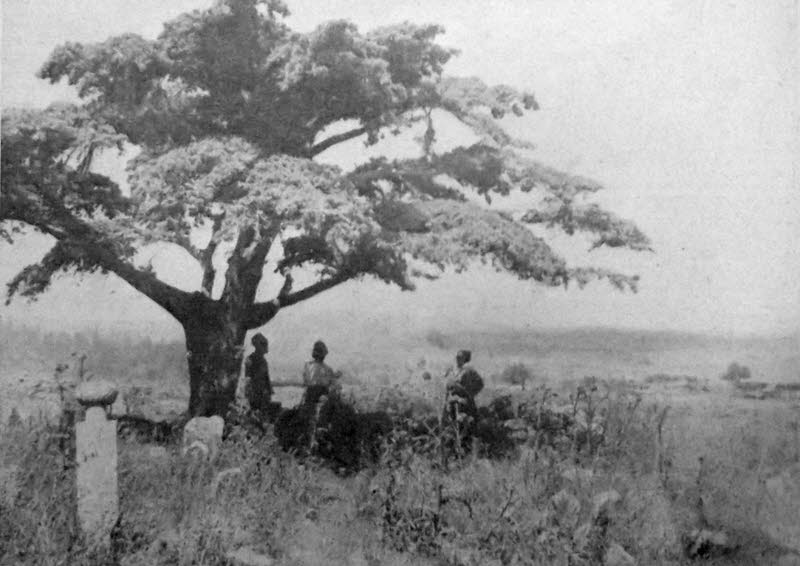

things but the censor forbids. The Turkish snipers are the very devil, I caught

one up a tree in a sort of green cage. His face was painted green and his rifle

and clothes. Truly a hoary old villain, and stacks of a-mution. Their fellows

pick off a lot of our men, they are very daring and cleverly conceal

themselves.

|

| Egyptian stamp, 1914 |

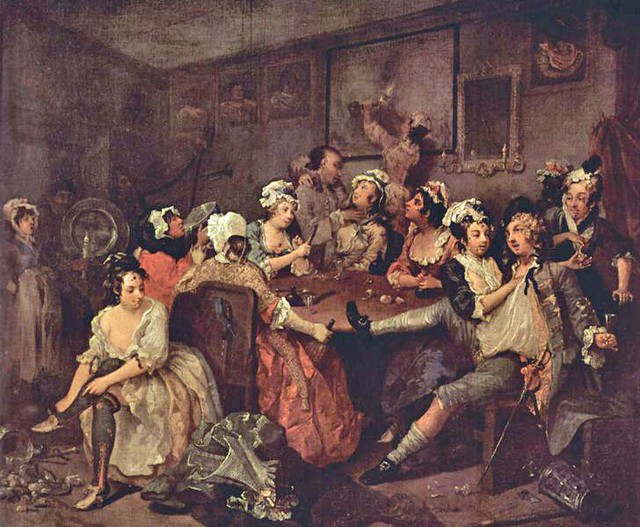

But we didn't half make some ground! The Turk (?) on the whole is quite

a gentleman in his fighting. His German master has taught him some of them some

of his dirty tricks.

A captain pal of mine who was hit close to where I was laying wounded,

was hit in the thigh by either an expanding or explosive bullet.

It simply blew the whole of his thigh out. He died in about half an

hour of loss of blood, and I couldn't move to help him. A corporal in my own

lo(?) was hit in the stomach by a similar bullet, with the same result. There

are tact's that happened to come under my notice. We ought to do the same, but

somehow we simply don't!

I know you are with us in spirit, so you will be glad to know we shall

be through the narrows soon. It's costly but it's going to be done.

I am going to stop now I am getting tired. I hope you can read my

scrawl, but writing is not quite so easy as usual just now. Kind thoughts to

you and regards to family.

Yours very sincerely,

Martin

I

apologize profusely for my absence all this time. I have not been at all well

these past six months; sometimes it is a struggle to even get up in the morning, and trying to write a blog post with my foggy brain is pretty much impossible.

I hope you will continue to stick with me, anyway.

~Psyche

_06.jpg)