|

| A map of their Adventures |

When I was seven

years old, my sister deemed I was finally Old Enough for Some Things. One of

them was the Seven-Year-Old Wonder Book,

which she started reading to me the night of my seventh birthday, the other was

Swallows and Amazons by Arthur Ransome.

Growing up

homeschooled in a place that doesn’t really approve of homeschooling, can often

be lonely. Some years we didn’t have any friends at all; they, or their parents

would make short work of the relationship. So often times, we had to make do

with ourselves…and various characters in books. There were weeks on end when my

sister was Sir Percy Blakeney and I was Sir Andrew and we were rescuing people

from prison during the French Revolution. Genres even crossed sometimes, with

the successful rescue of Sidney Carton from under the noses of the French. We

rewrote War and Peace with a happy

ending, amended The Chronicles of Narnia

so it could be played out with two children instead of four, and went off to

wander the slopes of Wales with Taran and Eilonwy in The Prydain Chronicles.

|

| Coniston Water in what is now Cumbria, one of the cheif influences behind the books Photograph by Paul Mcgreevy on Flickr |

So we really

weren’t as lonely as might be expected. We had each other, and we had books and

along with The Chronicles of Narnia, Away Goes Sally by Elizabeth Coatsworth,

and The Good Master and Singing Tree by Kate Seredy, there was

the Swallows and Amazon series.

It’s perhaps my

favourite series of all time. Though it’s hard to say, because there are others

that finish very close to it. I can say, however, that it is the most

engrossing and deceptively simple series I have ever read. Not only are the plots ingenious and unexpected, but each book is completely different from the last.

|

| Horning, Norfolk, setting for two of the books Photograph by Rob Fairweather on Flickr |

Starting in 1929,

the series follows a group of children as they grow up in England in the years

just before the war. There is no frivolous description, no romance to muck

things up, they are strictly stories of childhood…and what stories they are.

Many people are attracted to the books because of the things the children get

to do; they camp on islands, are allowed to use matches, go gold prospecting, sail

across the North Sea by themselves in a gale…among other things. The books are

also packed with masses of practical knowledge about wind and tides and

fishing, and include other professions that are almost dead, like charcoal

burning and wooden boat building.

|

| More breathtaking scenery form the Lakes District Photograph by Andy Rothwell on Flickr |

But the thing that

shines the brightest is how real they

are. Somehow they make ordinary things seem exciting; getting lost in the fog

becomes an epic adventure, and other things that might easily become boring,

like camping in a garden, aren’t. It’s hard to believe that these children and

this lake and those sailboats could have come from the imagination of

anyone…and to be fair, they didn’t. Arthur Ransome, the author (he was a good

friend of J. R. R. Tolkien, by the way), based it on his own childhood, and on

the adventures of children he knew.

|

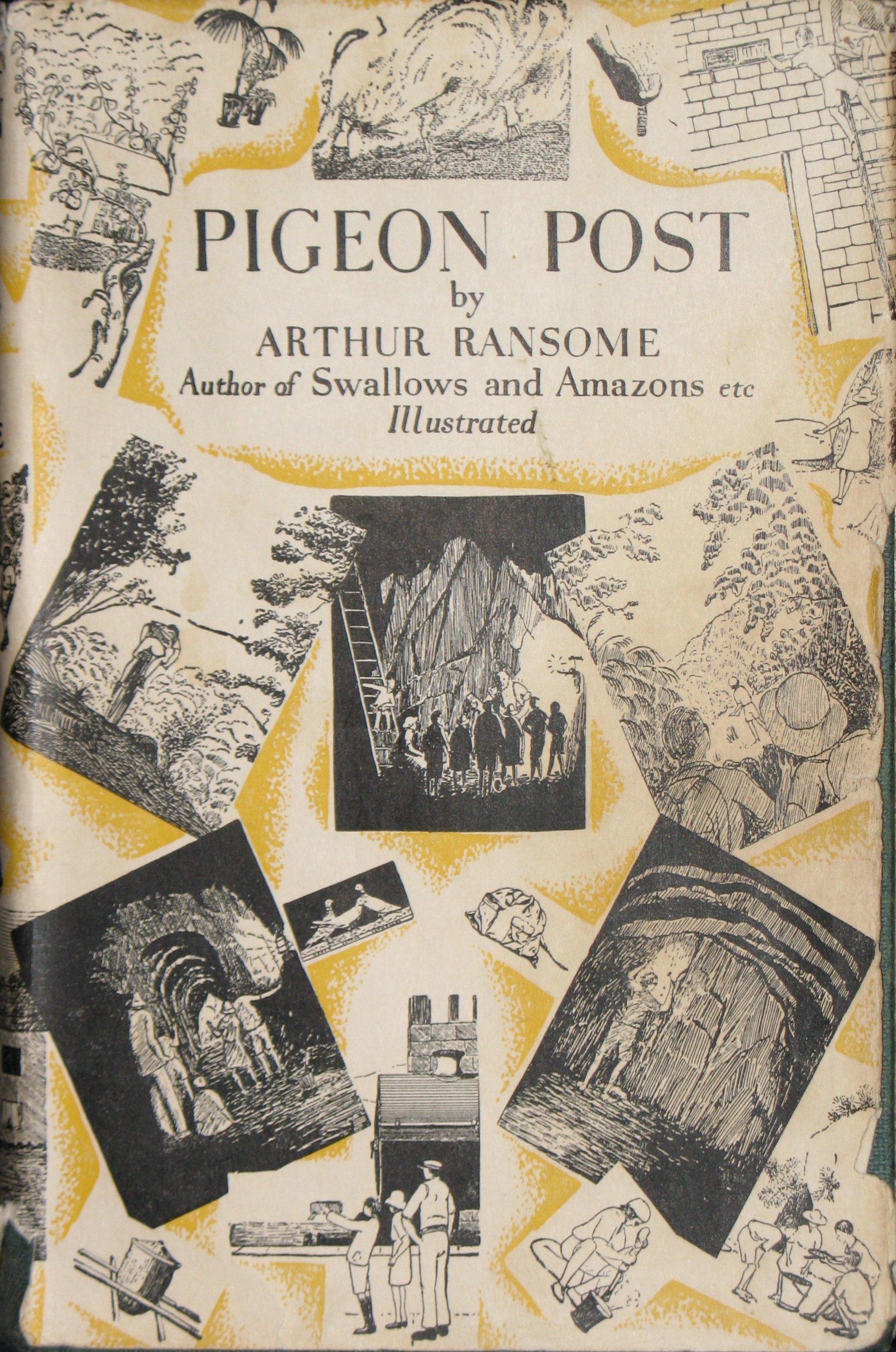

| A first edition of Pigeon Post, the first book ever to win the Carnegie Medal |

Consequently, the

characters in the stories are some of the most vivid I have ever read about.

They are so alive, that, despite their author, they begin to grow up as the

years pass. Almost imperceptibly they change through the series, their roles

shift, they become wise from their mistakes; some of them make plans for the

future…and quite suddenly, Arthur Ransome realized that his beloved children had

grown up on him and he stopped writing.

For some unknown

reason, because they are written for children, about children, the Swallows and Amazons series is dismissed

by most people as silly little children’s’ stories. In reality, there is

nothing silly about them. They are more serious and thought-provoking than

many ‘adult’ stories and painstakingly paint a picture of a world that once was

and never will be again: a world of river wherries and tall ships going down Channel,

a world of exploration without restriction, a world where children are capable and

can be trusted without lifejackets.

|

| Shotley in Essex, one of the starting off points for We Didn't Mean to Go to Sea, our favorite book in the series Photograph by David Parker on Flickr |

I would recommend

Arthur Ransome’s books to anyone, but somehow I doubt an adult could ever

understand what it was like to be first introduced to them at seven years old,

and to be able to grow up with them and watch them change just the way you

yourself were changing in the meantime. Perhaps, as an adult, if you grasp the

novel idea that children’s thoughts are just as important, and their feelings

just as sophisticated, as those of grownups, you may be able to appreciate

these books. Life isn’t all about who falls in love with whom, or gangsters in

dark cities, or going off to a war. There are the times in between, as well.

|

| The Nancy Blackett, Ransome's own boat, and the inspiration for Goblin |

Just to wet your appetite,

here’s an excerpt from Secret Water

one of the last books in the series, which I think sums up what the books are

like:

“I say,”

said Titty. “We ought to count days, like Robinson Crusoe.”

John bent

down and cut a notch in the flagstaff. “That’s for today,” he said. “Every day

we’ll cut another notch until the Goblin comes back…”

“And then

when we lie exhausted on the sand…” said Titty.

“Jolly wet

mud,” said Roger.

“We’ll see

a sail far away. And it’ll come nearer and nearer. And the captain will say, ‘Clap

your eye to a spyglass, Mister Mate.’ And the mate (that’s Mother) will say, ‘There’s

something moving on the shore. They’re still alive.’ And we will wave and try

to shout, but our parched throats won’t let us. And they’ll sail in, and we’ll

hear the anchor chain go rattling out. And then we’ll all sail away together

and see the island disappear into the sunset.”

“It may be

morning,” said Roger.